On the way to the workhouse

It’s nearly 70 years since the Social Insurance and Allied Services was formed, a system where all workers would pay a national insurance contribution, in return for benefits if they were sick, unemployed, retired or widowed. But where did people in dire financial straits used to turn for help when they needed it most?

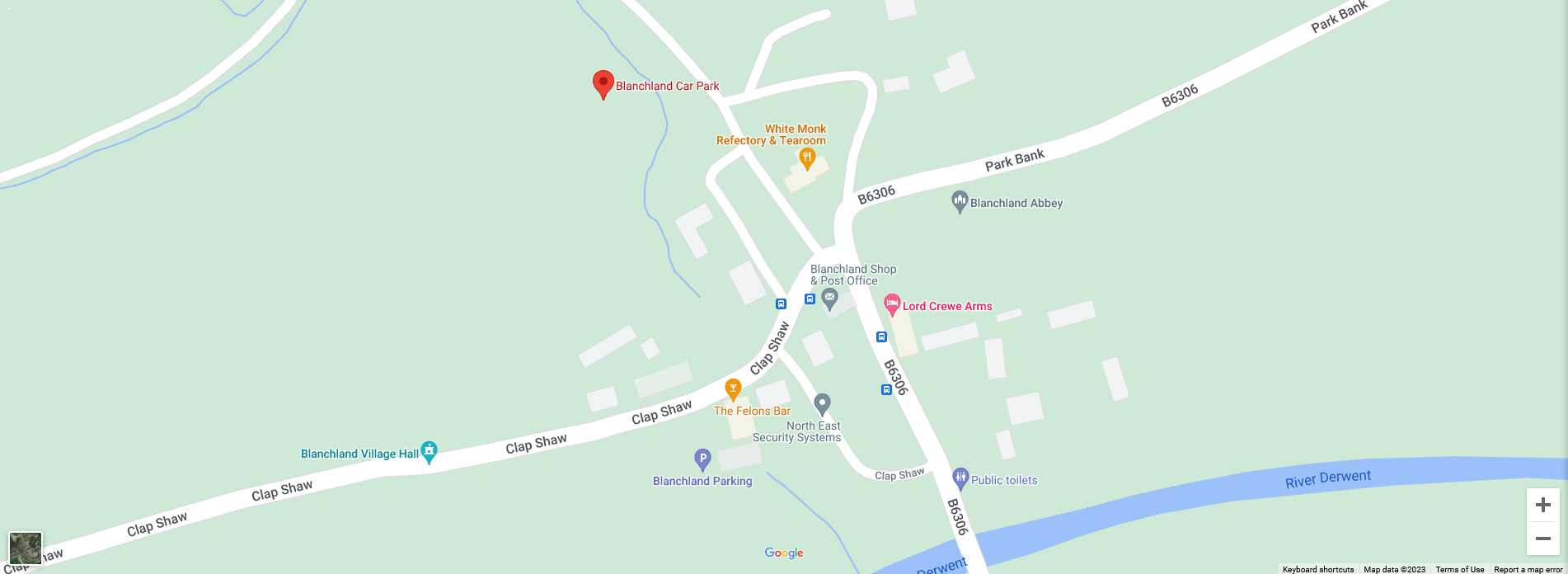

Lewis Nanney, the son of a Stanhope doctor, was working as a recently qualified medic in Blanchland in the early 1860s. The Lord Crewe Trust half-yearly accounts for 1861 show he was paid £5 “…for attending the sick poor in Blanchland” Photo – Allan Shaw

Life for lead mining families in and around Blanchland was often harsh; lead miners could expect to live to an average of 45 years or so; after that their health would start to fail as they succumbed to years of strenuous labour in the stale, damp air of the mines. For women, a local midwife would help bring a child into the world in the front bedroom, but there was little medical back-up if complications set in. And the children had to pick their way through serious childhood diseases such as chickenpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever and measles. Illness or the death of a father or mother could pitch the whole family into sudden destitution. The only hope for desperate housewives – if their families were unable to help out – would be Parish Relief, introduced with the Poor Laws during the reign of Elizabeth I.

The Poor Laws of the late 1500s were an important progression from private charity to a welfare state, where the care for the poor was embodied in law and was the responsibility of each town, village and hamlet. For more than 200 years, when families fell upon hard times through death, illness or injury, there was no automatic welfare safety net; they had to appeal to the charitable feelings of their own community to survive.

To qualify for Parish Relief, a needy person had to satisfy several criteria; you had to be born of legally settled parents, you had to be renting a property of more than £10 a year, or you had to be hired as a servant by a settled person for a continuous period of 365 days. Most labourers were hired from the end of Michaelmas week until beginning of the next Michaelmas, so household staff usually failed to qualify.

It’s difficult now to comprehend just how harsh life was for the poorest families in Blanchland; many would get by well enough, but a downturn in the fortunes of the lead mines could be the tipping point into poverty. Several letters sent to Lord Crewe’s Charity in the early 1830s and now deposited with Northumberland Archives give a glimpse into the hardships suffered when times got bad.

It looks as if the Lord Crewe Trustees responded to Rev Harrison’s suggestion that blankets would be a useful winter gift to the poor; this is a Newcastle Courant paragraph from 1833.

A letter to Lord Crewe’s Charity in April 1830 from Blanchland’s vicar, the Rev Robert Harrison, is in response to one such industrial depression. The Reverend had written to Lord Crewe’s Charity to ask for £100 to build a workhouse in the village: “…the lead works in the District have for some time past been in such a state of depression that the miners have not been able to earn more than one half of their accustomed wages, and in consequence of this reduction have been driven to seek parochial relief…”

He believes that Blanchland needs its own accommodation for the destitute, writing of the villagers: “…the want of a Poor House in their own Parish imposes upon them the necessity of sending those applicants, who stand in need of such accommodation to Hexham”.

At the time, Lord Crewe’s Charity was providing free school places for poor children in the area, and Mackenzie’s 1834 gazetteer mentions that the Charity traditionally delivered coal to 17 poor families in Blanchland to see them through the winter, and £10 of meat was distributed at Christmas.

A list of these donations and the recipients for Christmas 1875 and New Year 1876 is held in the Northumberland Archives:

But in 1832 it looks as if the village’s impoverished lead miners are still in need of more help; in November that year, Rev Harrison again appeals to the Trustees, asking this time that blankets be given out to the poor of Blanchland over the season of goodwill: “It strikes me they will be quite as acceptable as the Beef and Coals, and certainly will make a more lasting impression, in as much as they will impart comfort to the recipients eight hours at least of the four and twenty, and in constant operation when the latter are consumed and forgotten.”

Christmas 1840 was a hard time for 80 families around Blanchland according to this Newcastle Courant cutting.

An 1833 letter written on behalf of former soldier and Blanchland tenant John Hutchinson shows the immense pride ordinary working people took in being able to support their families, and the very public sense of failure and humiliation they felt when finally driven to accepting Parish Relief.

John had been injured in 1815 fighting the French at Quatre Bras in the Napoleonic Wars, and witnessed the fatal wounding of a son of a wealthy local landowner just a few paces in front of him. On his return to England he was called to the home of Sir Charles and Lady Clavering to give an account of the last moments of the young man’s life, and was “was liberally rewarded for his trouble” with a job in Blanchland looking after the plantations and hedging on the estate.

John had been told if he behaved himself, the job would be ‘bread for life’, and for 17 years he went about his work in Blanchland, earning a comfortable living for himself and his growing family. But suddenly, because of a decline in his health, John found two shillings a week were to be deducted from his wages… “which will altogether put it out of his power to maintain his family consisting of a wife and six small children.”

The letter continues: “… should the above named two shillings a week be kept off him it will lay him under the necessity of asking assistance from his Parish which would hurt his feelings much.” Whether John Hutchinson kept his two shillings a week is not clear; by the time of the 1841 Census eight years later, his wife Elizabeth is bringing up their children alone.

After 1834, responsibility for the poor moved from the immediate local community, with groups of parishes consolidated into Poor Law Unions. But the Poor Laws themselves stayed in force for almost another 100 years until they were finally abolished in 1930.For more information on the Poor Laws and workhouses, visit Peter Higginbotham’s excellent website, The Workhouse.