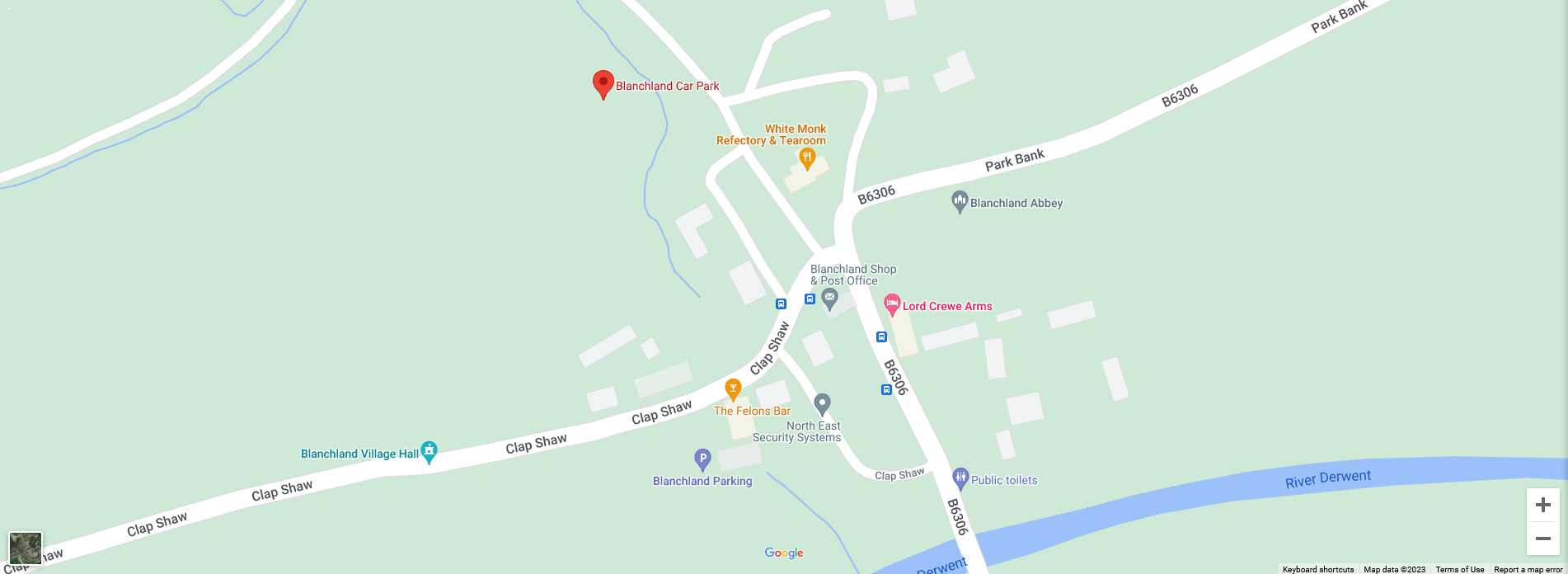

The road between Hunstanworth and Baybridge was dug out eight times, according to local school teacher Mr A P Clegg

It’s March 3 1947, and the children of Hunstanworth are trying to find the door to their school. Brenda Storey

In these days of milder winters, it comes as a shock when a sudden February snow flurry forces modern life to a grinding halt. But we can be fairly certain that all that will remain in a few days is some slushy white mounds by the dry stone walls. Winters in these exposed moorland communities were very different in years gone by; the Hunstanworth roads could disappear for weeks at a time under huge drifts of snow, and blizzards could rage for days.

The Hunstanworth school log books covering 1863 to 1893 give many examples of winters that were long and severe. In 1865 teacher Tom Wilkins reports snow drifts of four feet up against the school door, and a quick thaw resulting in a flood which forces him to teach the few pupils who have turned up in his own parlour. Even in May that year, the conditions are still miserably cold:

“In consequence of the wind blowing eastward the girls’ fire could not be lighted. The absence of the fires during these cold wet days makes the schoolroom almost unbearable and is the cause of much sickness (from cold and damp clothes) among the scholars. Myself and the mistress are often indisposed from the same cause.’

In March 1879, another teacher pens a desperate plea: “The snow is now and has been drifting terribly all night. The roads are completely blocked with snow. Not a single child has put in his appearance, even the woman who cleans the school and lights the fires has not been here. Surely this long and terrible winter will have an end some time.”

In January 1890 the teacher remarks: “Severe frost… cold seems to affect the children greatly, the pen shaking in their hands benumbed with cold.”

No problem reaching the telegraph wires to repair phone lines! Hilda Everitt

Today, older local people remember very vividly the extreme winter conditions, particularly of 1947 and 1963.

Hilda Everitt, who died on New Year’s Day 2009 at the age of 93, recalled that the people of Hunstanworth had a desperate battle for survival through the winter of 1947: “There was no coal delivered for six weeks, and the milk churns lay uncollected because not even a tractor or a lorry could get to us. We were completely cut off, and we didn’t have electricity in those days. We had to go into the woods to cut trees down for firewood. The men in the village set about digging a tunnel of snow to open up the road, hanging their coats on the tops of the telegraph poles because the snow was so deep! They also walked to Cartaway Heads taking pillowcases with them to collect bread from a baker’s van that met them on the A68. It was pretty grim.”Keen weather forecaster and local schoolmaster at the time, Mr A P Clegg, noted down some incidents which occurred over that winter which local historian Frederick Wade recounted in his 1967 book The Upper Derwent Valley:

“In the absence of coal, people burnt boots, furniture, anything combustible. The only light was from the fire when there was anything to burn.”

Schoolmaster Mr AP Clegg

“[Jim] Clegg and [Bertie] Short trudged 14 miles through snow five feet deep and brought back 36 loaves. When blizzards returned three men trekked to Carterway Heads and returned with food.”

“The funeral cortege of Mrs Murray of Blanchland was forced to leave the road with a hand-pulled sledge bearing the coffin and finish the journey to the church over fields, wall-high in snow.”

People survived by eking out their stores of food and fuel. But there were still occasional tragic tales even among these tough, independent North Pennine folk.

In January 1963, three elderly sisters, Minnie, Maud and Annie Pears, found themselves freezing cold and unable to get out of their Ramshaw home because of the 20 feet high snowdrifts that had made the valleys impassable. The Hexham Courant takes up the story:

“Policemen battled for five hours through terrific drifts to reach an isolated cottage at Ramshaw, near Blanchland, where three aged spinsters had been isolated for days.

“Two of the sisters, Miss Minnie Pears (74) and Maud (66) were found alive, but their 88-year-old sister Annie was dead. Five days earlier the sisters had refused the advice of their doctor to go to hospital temporarily.

“The rescue party crawled along the snow-packed roads and then, when it was impossible to go any further, borrowed a horse-drawn sledge from a farm and this took them three-and-a-half miles over the fells. Then nine local men man-handled the sledge another half mile until it was possible to see the cottage almost snow covered. The two sisters were in an exhausted condition and were taken eight miles by sledge to hospital.”

Nowadays we can turn up the heat in our four wheel drive cars, we can look out at the driving blizzards from our double-glazed windows, and we can always ‘text’ someone if there’s an emergency! But perhaps we should get some extra coal and food in… just in case.

An RAF helicopter delivers feed to the flock at Whitelees Farm. Davey Lonsdale.

The village men worked in twos to clear sections of snow in an attempt to keep the road open. Hilda Everitt

A Victim of the Freezing Cold

Gibraltar, uninhabited since Miss McDonald’s death in 1965

Local historian Frederick Wade, writing in 1967 in his book The Upper Derwent Valley, recounts this tragic event which had occurred two years earlier…

“On March 11th, 1965, an 83-year-old spinster died from exposure as she dug her way across the moor with a fireside shovel. The body of Miss Isobel McDonald was found by a shepherd, Mr Stanley Askrigg at 6am while on his way to work at a point where the track skirts a 100 feet drop to the River Derwent. The track led to her weekend cottage at Gibraltar on the moors above the source of the river.

He ran back to his cottage in the village of Hunstanworth to telephone the police. His next door neighbour, [Joe] Lonsdale and his son struggled back through the snow with him to stay near the body until the police arrived.

PC Craig of Edmundbyers was first on the scene. Next, two Northumberland County police arrived and together they dragged Miss McDonald’s body on a sledge up the snow covered hillside to the village.

After a snow plough had cleared the road, the body was taken in a van to Shotley Bridge Hospital.”