Primitive Methodists found strength in their religion

Life for ordinary Hunstanworth families in the 1800s could be fraught with uncertainty, the men often dying in their 40s from decades of breathing in the dust of the mines, the women and children left behind to work even harder or depend on other family members to take them in. Right across the North Pennines, Primitive Methodism gave people the spiritual resilience to endure whatever hardships came their way.

The people of Hunstanworth tended to be “Church” or “Chapel”, explained Hilda Everitt (1915 – 2009), meaning they attended St James’ the Anglican church in the village, or they went to the much simpler Primitive Methodist Chapel in Ramshaw, which was established at the end of Boltsburn Terrace in 1877.

The two Houses of God existed happily alongside one-another; in fact Hilda, whose parents the Armstrongs were “Church”, remembers regularly going to Ramshaw with her sister Mary Jane in the 1920s to help the four Pears sisters prepare for musical events. Hilda said: “Annie Pears played the organ at Ramshaw for many years, and as children we would help her by blowing the organ with bellows.”

Ramshaw Chapel’s roots run deeper than the 1877 commemorative stone plaque on the building’s front wall would suggest. According to Whellan’s Directory of 1856, a room close to the lead mines had been fitted out for worship six years earlier, and the Wesleyans and Primitive Methodists used it turn-and-turn about on alternate Sundays. A Sunday school for the children also ran there.

In a March 1880 agreement, the two Primitive Methodist Societies of Ramshaw and Shildon (another chapel between Hunstanworth and Blanchland) are handed over to the Shotley Bridge Circuit by Hexham. But the deal comes with eight conditions, the main one being that the two Societies must agree to pay all horse and trap hire from Shotley Bridge for the nine Sundays every quarter that they engage a travelling preacher.

Inevitably, the difficult roads and sometimes treacherous weather conditions result in an erratic supply of mobile ministers.

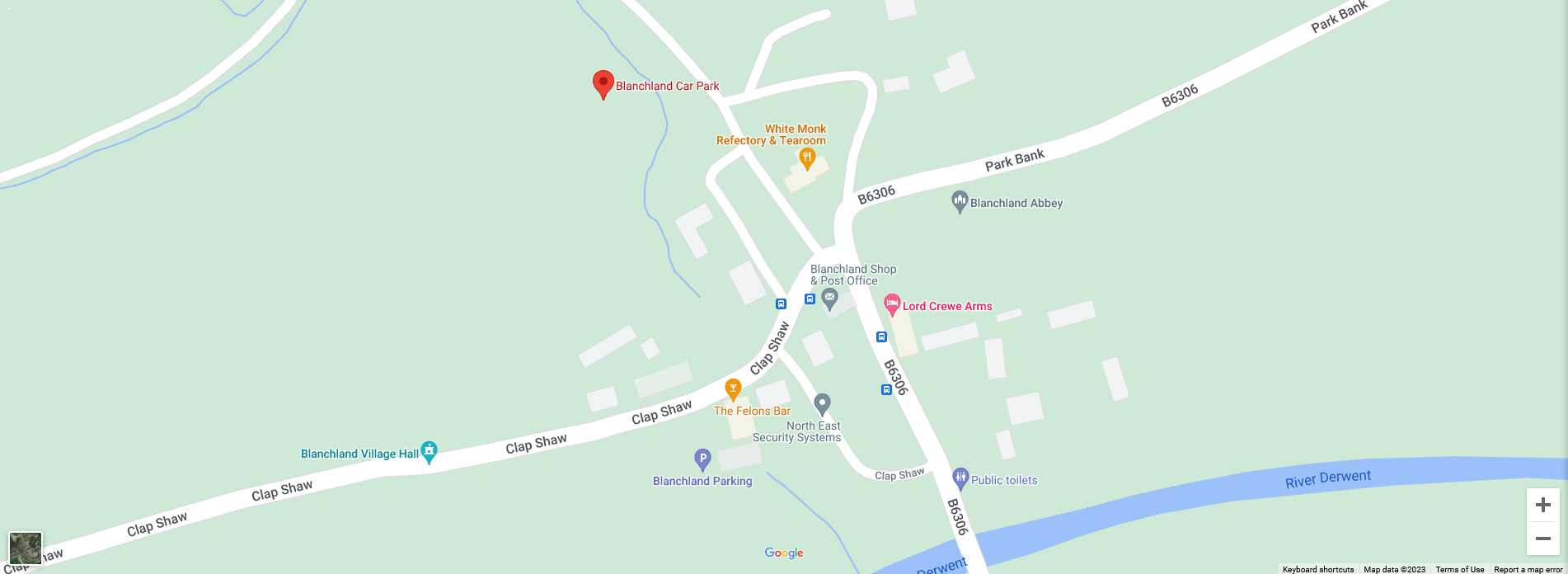

Inside Ramshaw Chapel today; enlargement shows detail of wall behind pulpit.

In 1899 a letter to the Shotley Bridge Circuit complains bitterly that Ramshaw and Shildon are not getting their travelling preachers as promised. The lengthy – and rather angry – letter of several pages refers to the original agreement and says: “You will notice that according to the above conditions we are entitled to eight sermons (including week nights) from the ministers – As many as six of those or two-thirds or nearly 70 per cent of the whole have been withdrawn – a very serious matter indeed.”

In his letter, William Pears grudgingly concedes that the Chapels have not always kept up their side of the bargain, which was footing the bill for the horse and trap. William (born 1857 – died 1945), like his schoolmaster father Thomas before him, ran a general dealers’ business on Jeffries Rake, selling all manner of goods to the lead mining families round about. A diligent pupil at Hunstanworth School, he’d gone on to be a school governor and PM lay preacher. And as secretary and treasurer at Ramshaw Chapel, his shopkeeper’s accounting skills really come into their own as he keeps careful note of the modest ingoings and outgoings in a small notebook.

The accounts books show that year on year activity at the chapel did not vary greatly. In 1922 the chapel’s income amounted to a few pounds for a musical service, a harvest festival and an annual donation by estate owner Edward Joicey. The Chapel may have been ministering to the spiritual needs of the congregation, but it was bodily comfort in those freezing Ramshaw winters that dictated expenditure; all the money went on oil, coke, coal, firewood, and cleaning – plus a bit kept by for tuning the organ.

Hymn-books and a Sunday School children’s reading book, all from Ramshaw Chapel. Books given by Cecil Davison

The congregation suffers the cold for nearly 50 years, until in the 1930s the chapel undergoes some renovation work; as a joiner and mason are engaged to carry out some repair work and a stove is bought for £30.

The Primitive Methodists may have trusted in the Lord for their salvation, but when it came to bricks and mortar, William Pears wasn’t taking any chances.

A 1939 cover note from Manchester’s Methodist Insurance Co Ltd shows that Ramshaw Chapel paid a 13 shilling (65p) premium to protect the building for £500 of damage, and this included pews, musical instruments, stained glass windows. It did not cover the pipe organ or blowing apparatus “connected therewith therein” though. And ironically neither did it protect the insured from “Acts of God” such as fire, lightning, aircraft or “Articles dropped therefrom”. Always cautious, William Pears’ accounts book for the war years records an extra premium paid out for “War damage.”

William Pears’ influence runs like a fine thread through what little remains of Ramshaw Chapel’s records. As the years advance, the handwritten entries grow increasingly spider-like. Eventually an entry for the annual trustees’ meeting on Feb 17 1945 says there is a proposal that “…a letter be sent to Misses Pears expressing our sense of profound loss to the church on the passing of their father and also our grateful appreciation of his very fine record of service at Ramshaw.” At 88, death has finally forced William to relinquish responsibility for the Chapel accounts.

A newspaper cutting from The Journal in October 1957 is the final chapter in Ramshaw Chapel’s history. The Chapel is closing for the winter, with only six in the congregation, and four of them are the Miss Pears, William’s spinster daughters. “I can remember when the chapel was packed,” Annie Pears told the reporter. “The lead mines were all going well in those days, and people would drive in by horse and trap from outlying places.” If William Pears had been looking down on his daughter Annie at that point he probably thought: “I never did settle up for those travelling preachers”…

Article from The Journal, October 1957. Cecil Davison was re-roofing Numbers 1 and 2 Boltsburn Terrace to the left of the Chapel when the photograph was taken. Cecil Davison

From the Hexham Courant, May 22 1880

A report of William Pears speech at a thanksgiving service… “Three years ago and for half a century previous to this time they were without a sanctuary in which to worship God. From the time that Primitive Methodism was introduced into Ramshaw, earnest and faithful prayers had been offered to the Almighty, imploring Him to open out a way by which they could erect a chapel. In the Spring of 1877, God answered these prayers. Through the kindness of the Derwent Mining and Smelting Co Limited, a piece of ground was secured. The total cost of the new building, harmonium etc, had been £300. This appeared to be a large sum to raise in a small village, and in the midst of depressed times; but after working earnestly for two years they must all rejoice and feel truly thankful that not a farthing of debt remained. From the beginning to the end of the undertaking he (Mr Pears) clearly perceived that they had been guided and aided by the hand of divine providence.”