Of Lambs and Lead Mines

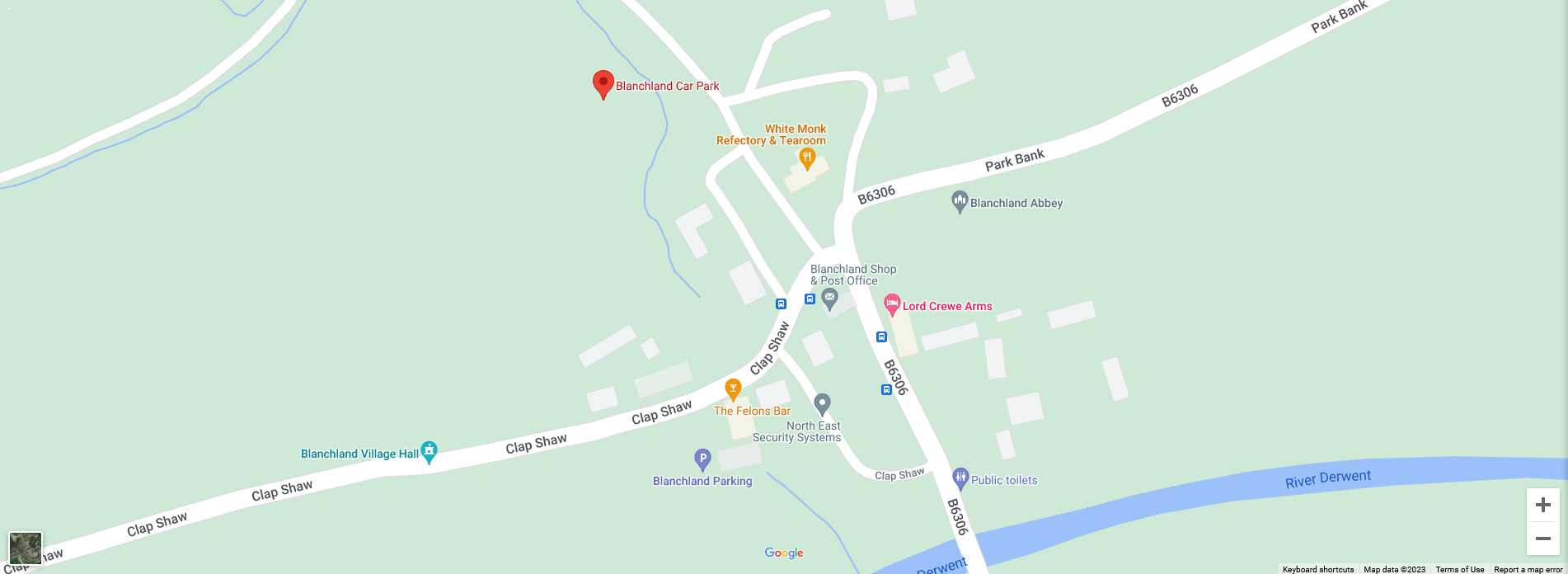

The nineteenth century was a boom time for the sleepy villages and farmhouses of the North Pennines. High quality lead had been mined in the area for centuries, but the introduction of new technology harnessing the power of water and steam meant production could be stepped up. For a few decades in the 1800s, hundreds of people flocked from other parts of the country to be part of Blanchland and Hunstanworth’s lead mining success story.

Hill farmers have also made a living from the moorlands surrounding the villages for hundreds of years, grazing their hardy flocks on the rugged hilltops and improved pastures in the valleys. Usually, lead mining families combined work in the mines with grazing livestock on an allotment, creating landscapes of small cottages dotted on the hillsides with field strips attached to them.

These pages describe aspects of the industries that shaped the area and dominated the lives of its people.

When ‘The Cornies’ Came

Shildon Engine House stands not only as a reminder of the once great lead mining industry of the Upper Derwent, but also the close – often stormy – relationship of two mining communities at opposite ends of the country.

The Engine House, built around 1806, is the only Cornish-style engine house in the North East of England. Although its massive Boulton and Watt steam engine only pumped water from the mines for around 10 years, the Engine House stands testament to an industrial boom period when technological developments, working practices, and even the people themselves were on the move between the lead mines of the Blanchland and the tin and copper mines of Cornwall.

Four letters which are almost 200 years old give an insight into the mines and mining technology which spanned the length and breadth of Britain and the engineering know-how that was shared.

The correspondence originally belonged to Shildon resident William Deans, engineer for the Derwent Lead Mines in the first quarter of the 19th Century, and has been passed down to his Great-great-granddaughter Meryl Hirons of Northampton.

The earliest letter – more a note written in November 1814 – is to Deans from Frederick Hall of local lead mine owners Easterby, Hall and Company and later the Arkendale and Derwent Lead Mines Company.

Frederick Hall is credited with giving the mines the overhaul they badly needed at the time, integrating operations around Blanchland and Hunstanworth so that they shared “watercourses, reservoirs, roads and other facilities and accommodations.” He also introduced a Miner’s Fund, built the area’s first crushing mills and replaced upright flues at the smelt mills with more cost-effective horizontal flues.

Seven years later, the influential Frederick Hall has taken on William Deans’ son James as a mining agent – not at Shildon, but at Newham near Truro. In James’ letter to his father, everything about Cornwall in 1821 is new and strange to the young man who has grown up in Blanchland: “The agents here are all call’d Captains – I am Captain Dean.”

What the well-dressed Cornish miner was wearing in 1866 – the year of ‘The Cornie Row’ in Blanchland.

The Cornish term ‘Captain’ for mining agent would become familiar around the mines of the Upper Derwent a generation later. As the tin and copper mines fell into decline, there was lead aplenty in the North Pennines; the population of Blanchland and Hunstanworth would rocket from around 200 apiece to more than 700 in the 1850s as the Cornish, upped sticks and trekked the 500 miles north and the mining companies moved their most trusted men up to run operations. They weren’t the only people on the move; workers from mines in Flintshire, Scotland, Mary Tavy in Devon and Arkengarthdale in Yorkshire converged on the Blanchland area.

James Paull settled in Hunstanworth. Bill Bates

Bill Bates of Slaley’s Cornish ancestors, the Paulls, came to Hunstanworth in the early 1850s, and Captain John Paull spent nine years as lead mining agent before moving to Wales to continue his career. His brother James Paull arrived in the area around the same time, and put down roots by marrying local girl Jane Eddy. He, Jane and their family of 11 children lived in one of the lead miners’ smallholdings at Boltshope Park, James dying in 1883 – 32 years after making the trip north for work.

James may have found life good here, but an influx of outsiders which quadrupled the population was bound to create tensions, especially when the lead mines began their gradual decline.

The ill feeling spilled over into violence in November 1866, when a disagreement with landlord George Mawson in the Miner’s Arms pub at Baybridge degenerated into full-scale battle. Around 27 ‘Cornies’ felt that Mr Mawson was more hospitable to the locals than them, and – as we say today – they trashed the place. Lead smeltor George Wilkinson of Ramshaw and miner Joseph Murray of Jeffrey’s Rake had gone into the pub for a quiet pint, when the mob burst in and started their wrecking spree. They both suffered head injuries in the fray, but managed to make a run for it to Blanchland to get PC Beattie.

Amateur poet George Carr takes up the tale in his 1890s poem Bonnie Blanchland:

"When Beattie came upon the scene,

They threw him on the fire:

The blue-coat servant of the Queen

No reverence could inspire.

He reasoned thus: "If numbers great

Gives them the upper hand,

I'll go to Blanchland, and checkmate

Them with a bigger band."

Then soon the scene was chang'd, and those

Who valiant were before,

Fell down before their victors' blows,

Besmeared with streaming gore.

Now, why the Cornies acted so

I may not tell you now,

But ever after this, you know,

'Twas called the "Cornie Row."

Eight Cornish miners, including Joseph Trethewey, William Trewartha and Bennett Toy, appeared at Hexham Police court charged with… “having riotously assembled… so as to disturb the peace and with injuring and damaging the Miners’ Arms Public House at Baybridge.”

George Carr sums it up:

"'Twas talked about in after days,

As of a great event,

And feelings bad, in various ways,

Showed till the Cornies went."

The Miner’s Arms, Baybridge in the 1890s… scene of ‘The Cornie Row’ of 1866. Bill Bates

Thanks go to Meryl Hirons for kindly copying her ancestor’s correspondence, and to Bill Bates of Slaley for the old photo of Baybridge.