The Irish Stone – believable or just blarney?

Gather round, while I tell of spells and charms being cast long ago, of mystical potions and ancient amulets… in these modern times, the superstitious beliefs of our forebears are more likely to be met with guffaws of derision than gasps of wonder. But not so long ago, magic and superstition went hand-in-hand with everyday life, and people believed that ancient powers could be harnessed to influence events.

Adders were called The Earl of Derwentwater’s adders when people believed they only appeared in the area after his beheading in 1715.

North East rural communities had their own particular brand of magic in the shape of Irish stones. These were stones – unsurprisingly from Ireland – which were thought to have special powers to cure venomous infections, both in people and (perhaps more importantly for farmers) cattle. In times when poor people had to pay hard cash for a doctor’s or a vet’s visit, Irish stones were believed by some to be the antibiotics of the 18th and 19th Centuries.

In their 1949 book Encyclopedia of Superstitions, Edward and Mona Radford say that our ancestors believed these stones had to be brought from Ireland and never be allowed to touch English soil. If the stone was used on wounds by the hands of an Irish man or woman, so much the better.

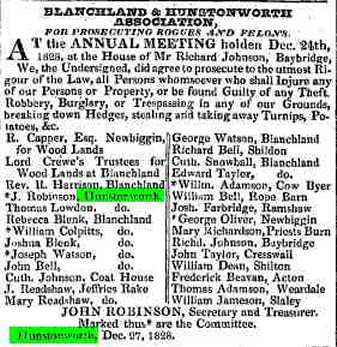

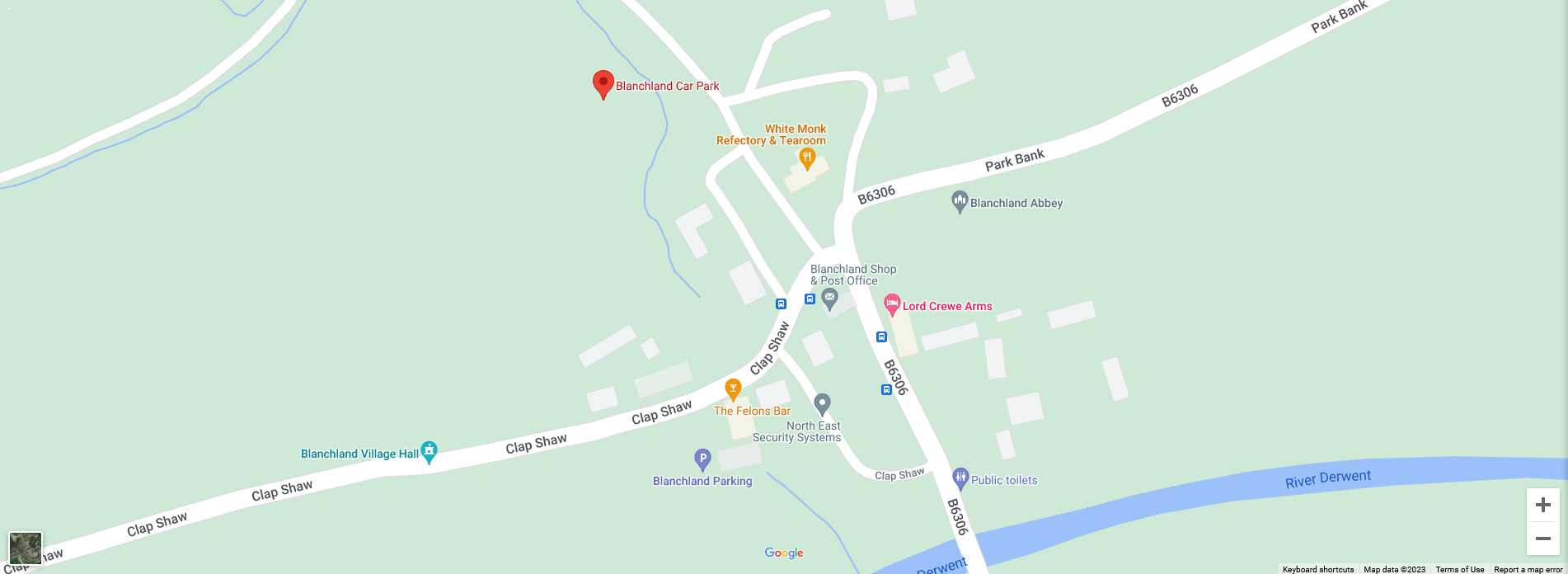

An article by William Morley Egglestone, known as the Weardale Historian, in the March 1889 issue of the Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legends tells of one of these Irish stones that was in the possession of a Blanchland resident…

“In the month of October, 1884, I handled a once famous Irish stone which was in the custody of a good dame, residing beneath the shadow of the old Abbey of Blanchland, in Northumberland. On inquiry being made for the charm, a search was made in the corner of a drawer, and a bag, yellow with age, was carefully brought out, unfolded, and its contents – the Irish stone – exhibited.

“The good lady was seventy-eight years of age, and the charm was in the house when she married into it, forty-nine years before. It was the property of her husband, who died about twenty-nine years since, and she had heard him say that the stone belonged to his father.”

From this description, and from a match with other records, it sounds as if the stone belonged to ‘Old Betty Horsely’, or Elizabeth Horsely Beck, who according to a Hexham Courant article of June 30 1888 lived at The Corner in Blanchland, and featured in the newspaper at the time because she was an ‘incredible’ 82 years old.

The stone was famed in the area, says Mr Egglestone: “During her time it had been lent “all up and down” to individuals who had got envenomed, or had cattle so suffering, and she could testify that its application stopped inflammation, as she remembered effectually rubbing the face of her husband, who had been stung by a bee.”

He goes on to tell that the charm was supposed to be from Connaught, is a water-worn flint, lentiform – lentil-shaped – and dark with white blotches. “This Blanchland charm had not been used for several years,” he said, “but within the good lady’s remembrance it was of considerable repute, it being the only Irish stone in the district.”

A charm against venom was a handy thing to have in the Derwent Valley, especially following the beheading of the Earl of Derwentwater. Egglestone goes on to recount another popular piece of folklore in the area at the time: “Previous to the unfortunate Earl suffering death no adders or other reptiles, so the story goes, haunted the banks of the Derwent. However, immediately the head of the Earl rolled from the block in 1715, adders appeared in abundance on the river’s banks almost from the source of the stream to where it enters the Tyne. Hence the Blanchland charm was held in very high estimation, numerous applications being formerly made for it.”

Meggie Peadon from a story in the Evening Chronicle in 1961.

Being able to charm away infection with the use of stones or other items such as gold rings seems to have been a belief that continued well into the 20th Century. Daisy Hall, who lived at Boltshope Park for 45 years from 1932 when she arrived as a young married woman, said that Meggie Peadon of Ramshaw, a lady with a sharp nose, grey hair and rather old-fashioned clothes, was said to have the ‘charm’. “The ‘charm’ only came when the moon was waning,” said Daisy, “Meg would take a stone from the wall – she wouldn’t let you see it – but by rubbing the infected area with it, people said she could charm erysipelas away.”

Erysipelas – otherwise known as St Anthony’s Fire – was a facial infection which spread across the nose and cheeks as a hot, painful and shiny rash and could force swollen eyelids shut. Related to today’s relatively mild throat infections, erysipelas was a leading cause of death in the 1800s, particularly for women who had just given birth.

The late Lily Lonsdale of Hunstanworth, who sadly died in January 2008, told how Meggie Peadon once seemed to have charmed away a nasty infection in her eye. “My eye had been closed up and very painful,” Lily had said, “Meggie was known in the area for doing these things, and she came down and rubbed my eye with a stone in her hand.” Coincidence or not, Lily’s eye inflammation cleared up.

Was Meggie using the famed Blanchland stone that had apparently cured envenomed cattle and their owners alike decades earlier? Is it tucked away into a dry stone wall somewhere, just waiting to cure infections again? The pharmaceutical industry had better beware…